Radar Tracking and Telemetry Primary tracking

Peter Morton : Fire across the desert 1989

THE PRECISION RADARS: FPS-16

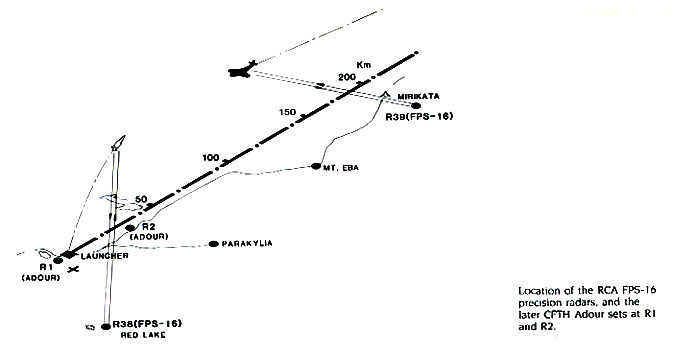

Late in 1959 two of the very latest American precision radars arrived at Woomera and were installed in special buildings. They were C-band (6 centimetre wavelength) FPS-16 radars. They had little in common with the wartime British No.3 Mk 7s which they replaced, except that both were tracking pulse type radars. Otherwise they were vastly more powerful and sensitive, particularly when the target was fitted with a small C-band transponder. And they were much more precise and versatile, producing a digital output well suited to automatic data processing and recording. For all these reasons the FPS-16 radars were useful for trajectory recording and for critical safety tracking. They were by far the biggest instrument ever installed on the Woomera Range: each one filled most of a two-storey building with the tracking dish on top. Like much of the upgrading of Woomera instrumentation that began in the late 1950s, the new radars arrived for Blue Streak. In August 1957 a combined RAE-be Havilland mission arrived at WRE to discuss the big project. when it became apparent that very exact tracking of the missile would be essential so that its engines could be shut if the missile threatened to transgress its flight corridor. The MTh was just not precise enough for this job. Soon afterwards WRE's two top instrumentation experts. Boswell and Kirkpatrick, discovered during an American visit that ranges such as White Sands and the Atlantic Missile Range were relying heavily on the recently developed FPS-I6 radars, both for safety tracking and for down-range trajectory measurement in their ballistic missile trials. And so two were acquired for Woomera. one to go at the rear of the Blue Streak launcher and one about 170 kilometres down-range. These extremely intricate devices were not cheap—to the journalists of the day they were the 'million pound radars'—yet they cost the joint project nothing apart from the not inconsiderable price of spares, documentation, building and installation work. America presented them as a gift. part of the Mutual Weapons Development Project, a defence aid agreement.'

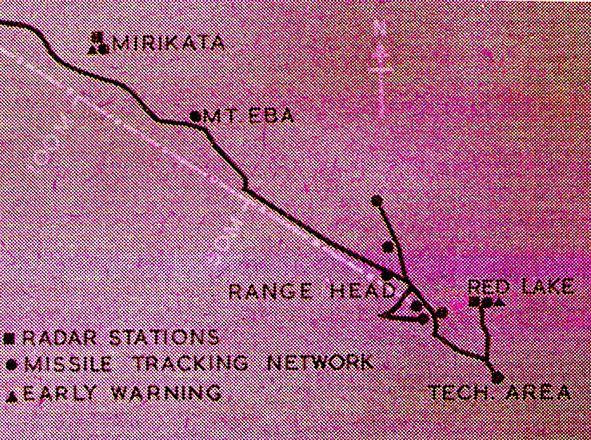

The rear FPS-I6 site (R38) was at Red Lake. just north of the long-abandoned Range A.

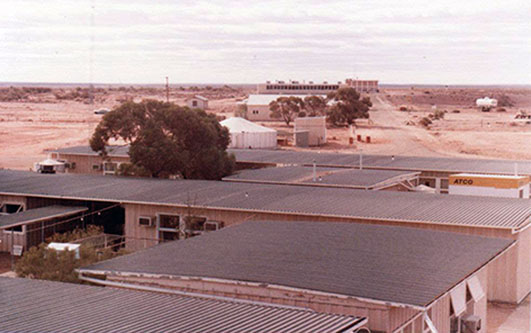

The down-range site (R 39) was 170 kilometres from the Blue Streak launcher, past Mt Eba. Here was also installed other Blue Streak instrumentation. including ballistic cameras and telemetry receivers. together with living quarters. and the complex was called Mirikata, another Aboriginal word meaning 'morning star'.

(Mirikata Historic Radar Site.

Following early failures at long range detection John Strath and others turned their attention to radar experiments related to missile launch and re-entry phenomena.

TTCP, a quadri-lateral technical cooperation program, was established in 1965 and in 1968 the US participants became aware of the work being conducted by John and his team.

This led to a small group of Australian scientists being briefed into the highly classified US program and, in time, to a proposal for a collaborative program between the US and Australia on Over the Horizon Radar.

John assembled a small team and started the arduous task of developing a plan and marshaling support in Canberra.

In addition to theoretical studies, an experimental trial known as Project Geebung was undertaken to demonstrate that the propagation paths were indeed suitable. This involved both one-way and two-way propagation experiments between Mirikata on the Woomera Rocket Range and Derby. )

Mirikata and Red Lake both survived the Blue Streak cancellation because the FPS-16s were fully employed on other long range trials such as Blue Steel. Black Knight and the European satellite launcher which was then on the horizon.

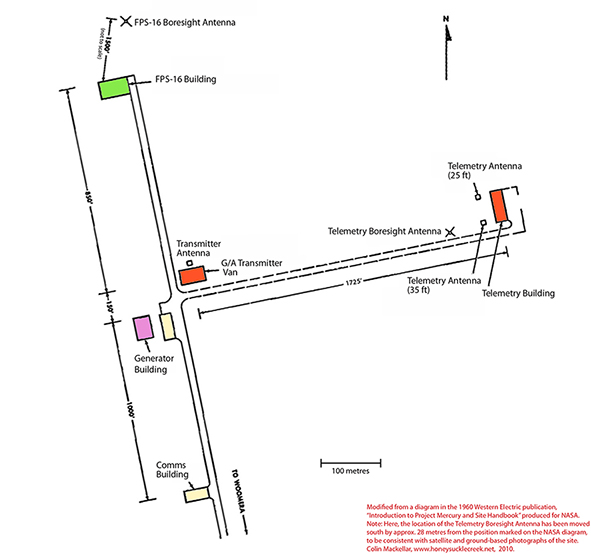

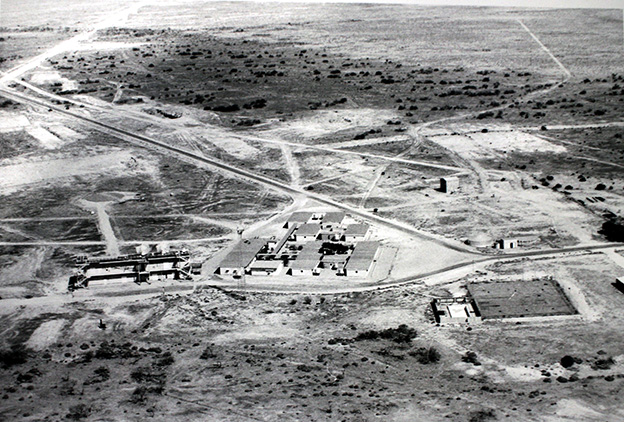

Studies were already in progress on the likely coverage and accuracy of the FPS-I6 radars for tracking Bloodhound Mk 2 and other forthcoming long range guided weapons as well, and their targets. And the Americans had been promised some return for their generosity. The radars could be used for certain satellite tracking missions until the NASA Deep Space station at Island Lagoon was brought into operation. By 1960 the staff of Ranges Group had finished their acceptance tests and taken them over from the RCA Installation team. Extensive performance tests of the two radars continued for a few years. but in the meantime they were drawn more and more into trials. The earliest application to a weapon trial was Blue Steel: on 30 November 1960 R38 was used on the first of the full scale missile trials, a drop of an unmotored vehicle from a Valiant aircraft. The following year Red Lake took part in the first US manned space flight program. Mercury. when NASA installed a radio communications and telemetry receiving station alongside the radar building. And thus it was that Red Lake became a component of the global tracking network used in the historic space orbit by John Glenn on 21 February 1962. During the decade following. both FPS-I6 radars formed part of the safety tracking systems for all the space vehicles launched from Woomera: Europa, WRESAT and Black Arrow.

For the Dazzle re-entry physics program of the later Black Knights. they enabled the special optical and radar Instrumentation to acquire the elusive head as it entered the atmosphere. But their bread and butter application was to trials of the long range guided weapons. not only Blue Steel but Bloodhound Mk 2. VR725 and Sea Dart as well.

Black Knight Dazzle Project 1964

Black Knight Dazzle Project 1964

They were little used for short range and low altitude trials as they were too far from the rangehead for these. and with their narrow beams they needed time and good acquisition data to find and lock on to their targets. The two FPS-16s were not operated by Army servicemen like the No. 3 Mk 7s but by civilians. initially of Ranges Group. Because technical staff were in short supply during the boom period of the early 1960s, private firms under contract operated and maintained the radars: first Amalgamated Wireless Australasia between 1962 and 1975. and then Palmy}, The FPS-I6s became superfluous during the run-down because they were expensive to maintain and operate and had no function in the small post-project work of the Range. However, they avoided the ignominy of being sold off for scrap. The one at Red Lake was sold for $30 000 to the US Air Force. This might look like sharp practice considering it had been a gift. but the project had paid the US very much more than that amount over the years for documentation, upgrading and spares. The buildings were eventually sold off to the Roxby Downs station on whose land they stood. The Meditate radar went to the Radar Division at Salisbury for experimental work and Mirikata itself became a motel. Thus ended a period of nearly twenty years in which the two FPS-I6 radars had clearly held top status among the many instrumentation systems at Woomera. The disposal of the FPS-16 radars in 1979 was probably inevitable. There were two other precision radars on the Range which could cope with navigation, safety tracking and acquisition for the very modest short range trials that were envisaged for the future. These other radars were the two French CFTH Adour sets at posts RI and R2, and they had been there since 1968. Early in 1962, soon after the FPS-16 radars were commissioned. a study had begun on what to do with the obsolete No. 3 Mk is and the MTS. Not only were they becoming more difficult to maintain but performance was deteriorating. Then they needed a total staff of thirteen to operate and maintain them. and staff was in short supply. Yet they had to go on being used in day to day trials at relatively short ranges and altitudes, for target navigation. for safety tracking and to provide acquisition aids. The FPS-16 sites, established for long range trials, were just too tar away. A submission of March 1965 recommended that new radars be obtained to replace the three No. 3 Mk 7 radars. six MTS sets and another interim surplus British radar. Yellow River. on loan to the Range." As a result, a joint UK-Australian team of radar experts visited Paris, Rome and an Italian range in Sardinia, and narrowed the choice down to two radars: the French Adour or the Italian Selenia. Tenders were invited and the one from the French Compagnie Francaise Thompson-Houston (CFTH) finally accepted for two Adour radars. at a cost of about £1.3 million. By lune 1968 the two radars had been delivered. installed In their prepared sites. the data links connected and the whole system commissioned. The Adour radar was sometimes regarded as a poor man's FPS-16. and certainly it lacked the latter's very high performance. Still. it could track a typical missile without a transponder up to 150 kilometres or so. which was adequate for its Woomera role, while its accuracy was more than sufficient for navigation, safety tracking and acquisition purposes. And the Adour had the edge over the FPS-I6 operationally. It used transistors on plug-in printed circuit boards rather than valves. which made it more reliable and easier to service, and it did not require a long warm-up time. A team of six was enough to operate and maintain the two Adours, against eleven or so for the two FPS-I6s.

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 19 autres membres